Hockey Analytics

Apply data science to hockey and broader sports analytics

Project maintained by justinjjlee Hosted on GitHub Pages — Theme by mattgraham

Better than coin flips? Money line and market expectation in NHL

When creating a framework or a model explaining team performances, we narrow down the scope of the evaluation criteria (e.g. amount of information) to derive more interpretable trends and phenomena. Doing so limits the available information that otherwise can be reflected and helps make better prediction (e.g. you could have been right 61% of the games, instead of 60%).

Market expecation theoretically reflects all available information. Applying a concept in finance called Efficient Market Hypothesis, we can assume that the overall prediction tends to be more accurante on average than any single agent or model.

The analysis below evaluates the predictive power of the market expectation. Using the publicly available sports betting data (specifically on money line), I answer following questions,

- How good is the market predicting the outcome of each game?

- Is there a disparity (heterogeneous) in predicting outcome, specific teams or win/loss?

- Is the market better and more confident in predicting wins than losses?

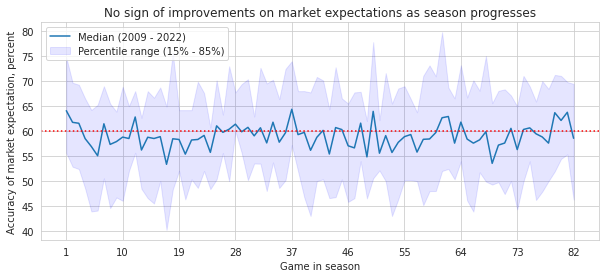

- As the market accumulates more information about each team as each season progress (i.e. as each season progress and more games are played), does the market make better prediction?

This analysis serves as a first part of NHL team performance analysis using NHL data.

import pandas as pd

pd.options.mode.chained_assignment = None

import numpy as np

from datetime import datetime, timedelta

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

def func_df(df, year_start, year_end):

# function to process the data

# Adjust column names

# multi-row data pull for python assings the first column.

# More sophisticated method is to start the data pull row at 2nd row

df.rename(columns = {'PuckLine' : 'PuckLine_spread',

'Unnamed: 11' : 'PuckLine_MoneyLine',

'OpenOU' : 'OpenOU_spread',

'Unnamed: 13' : 'OpenOU_MoneyLine',

'CloseOU' : 'CloseOU_spread',

'Unnamed: 15' : 'CloseOU_MoneyLine',

"Close OU": "CloseOU",

"Open OU" : "OpenOU",

"Puck Line":"PuckLine",

"Clos":"Close"

}, inplace = True)

# For now, use the following column:

df = df.loc[:,['Date', 'Rot', 'VH', 'Team', '1st','2nd', '3rd', 'Final', 'Open', 'Close']]

# Some adhoc data cleaning:

# For 2021 season data, final score is marked 'F' and at 3rd period score

if 'F' in df.Final.unique():

df.loc[(df.Final == 'F'), 'Final'] = df[(df.Final == 'F')]['3rd']

# Need to convert the columns to integer

df['Final'] = df.Final.astype(int)

# Process date time --------------------------------------------------------

# create year column, based on the month-date integer column

# Season starts around October, which the length of each element is 4,

# The new calendar year, the length becomes 3

df['yr'] = str(year_end)

df.loc[([len(str(iter)) == 4 for iter in df.Date]), 'yr'] = str(year_start)

df['yr_season'] = str(year_end)

# start with dummy place

df['gameDate'] = datetime.today();

# Create date in string format similar to NHL data

for iter, value in enumerate(df.Date):

# pad in 4-digit month/date format to extract

temp_ls = str(value).rjust(4, '0')

lst_mo = temp_ls[:2]

lst_day = temp_ls[-2:]

# Create date format

iter_date = df.yr[iter] + '-' + lst_mo + '-' + lst_day

iter_date = datetime.strptime(iter_date, '%Y-%m-%d')

df.loc[iter, 'gameDate'] = iter_date

# Calculate week start

df.loc[iter, 'gameDate_wknd'] = iter_date - timedelta(days=iter_date.weekday())

# Process team name --------------------------------------------------------

# Make sure all teams are included (there may be some new teams)

#Team = list(df.Team.unique())

Team = ['Pittsburgh', 'TampaBay', 'SeattleKraken', 'Vegas', 'NYRangers',

'Washington', 'Montreal', 'Toronto', 'Vancouver', 'Edmonton', 'Chicago',

'Colorado', 'Winnipeg', 'Anaheim', 'Ottawa', 'Buffalo', 'Florida',

'NYIslanders', 'Carolina', 'Dallas', 'Arizona', 'Columbus', 'Detroit',

'Nashville', 'LosAngeles', 'NewJersey', 'Philadelphia', 'Minnesota',

'Boston', 'St.Louis', 'Calgary', 'SanJose', 'Phoenix', 'Atlanta',

'WinnipegJets', 'Tampa', 'Arizonas', 'Tampa Bay', 'NY Islanders'];

team_tri = ['PIT', 'TBL', 'SEA', 'VGK', 'NYR',

'WSH', 'MTL', 'TOR', 'VAN', 'EDM', 'CHI',

'COL', 'WPG', 'ANA', 'OTT', 'BUF', 'FLA',

'NYI', 'CAR', 'DAL', 'ARI', 'CBJ', 'DET',

'NSH', 'LAK', 'NJD', 'PHI', 'MIN',

'BOS', 'STL', 'CGY', 'SJS', 'ARI', 'WPG',

'WPG', 'TBL', 'ARI', 'TBL', 'NYI'];

df_tricode = pd.DataFrame(data = {'Team':Team, 'team_tri':team_tri})

# Join with the data

df = df.join(df_tricode.set_index('Team'), on = 'Team')

# Drop useless columns

df.drop(labels = ['Date', 'Rot', 'Team'], axis = 1, inplace = True)

# Process game for each team records

#assumes the game is in order (very important)

df_home = df.loc[df.VH == 'V', :].reset_index(drop = True)

df_home.drop(labels = ['VH'], axis = 1, inplace = True)

df_away = df.loc[df.VH == 'H', :].reset_index(drop = True)

df_away.drop(labels = ['VH'], axis = 1, inplace = True)

df_fin = df_away.join(df_home, lsuffix = '_away', rsuffix = '_home')

# Create game ticker following the rule - following the data rule that is

# used for the NHL data

df_fin['gameIdx'] = '';

# The tricode of team orders (visiting team) - (home team)

for idx, value in enumerate(df_fin.team_tri_home):

# away, home, date

df_fin.loc[idx, 'gameIdx'] = df_fin.team_tri_away[idx] + '_' + \

df_fin.team_tri_home[idx] + '_' + \

str(df_fin.gameDate_home[idx].strftime("%Y-%m-%d"))

# Compare game outcome and market prediction -------------------------------

df_fin['win_home'] = 0.5

df_fin['win_away'] = 0.5

# Home team wins

idx_rows = (df_fin.Final_home > df_fin.Final_away)

df_fin.loc[idx_rows, 'win_home'] = 1

df_fin.loc[idx_rows, 'win_away'] = 0

# Away team wins

idx_rows = (df_fin.Final_home < df_fin.Final_away)

df_fin.loc[idx_rows, 'win_home'] = 0

df_fin.loc[idx_rows, 'win_away'] = 1

df_fin['win_ml_home'] = 0

df_fin['win_ml_away'] = 0

# Predicted home team will win (negative money line)

# Positive == Underdog (market expects to lose)

idx_rows = df_fin.Close_home < df_fin.Close_away

df_fin.loc[idx_rows, 'win_ml_home'] = 1

df_fin.loc[idx_rows, 'win_ml_away'] = 0

idx_rows = df_fin.Close_home > df_fin.Close_away

df_fin.loc[idx_rows, 'win_ml_home'] = 0

df_fin.loc[idx_rows, 'win_ml_away'] = 1

# This way, in future, instead of boolean, more continuous measure can be

# accounted for

# Boolean prediction match

df_fin['win_pred_home'] = 0

df_fin['win_pred_away'] = 0

# Predicted home team will win

idx_rows = df_fin.win_home == df_fin.win_ml_home

df_fin.loc[idx_rows, 'win_pred_home'] = 1

# Predicted away team will win

idx_rows = df_fin.win_away == df_fin.win_ml_away

df_fin.loc[idx_rows, 'win_pred_away'] = 1

# rename game period stats

df_fin.rename(columns = {'1st':'game_1st', '2nd':'game_2nd',

'3rd':'game_3rd', 'Final':'game_final',})

return df_fin

Import data from websites

Import data from websites

# Scrape data of the year available

last_yr_edge = 22 #2022

vec_yr = range(7, 22)

for iter in vec_yr:

str_yr_start = str(iter).rjust(2, '0')

str_yr_end = str(iter + 1).rjust(2, '0')

str_url = 'https://www.sportsbookreviewsonline.com/scoresoddsarchives/' + \

f'nhl/nhl%20odds%2020{str_yr_start}-{str_yr_end}.xlsx'

# Exception of COVID outbreak year

if str_yr_start == '20':

str_url = 'https://www.sportsbookreviewsonline.com/scoresoddsarchives/' + \

f'nhl/nhl%20odds%2020{str_yr_end}.xlsx'

print(str_url)

# Import data as needed

df = pd.read_excel(str_url)

year_start = (int('20' + str_yr_start))

year_end = (int('20' + str_yr_end))

df_prop = func_df(df, year_start, year_end)

# Join with the existing data

if iter == 7: # the first data

# Do not append the data

df_fin = df_prop

else : # append data as needed

df_fin = pd.concat([df_fin, df_prop])

df_fin.reset_index(drop = True, inplace = True)

https://www.sportsbookreviewsonline.com/scoresoddsarchives/nhl/nhl%20odds%202007-08.xlsx

/usr/local/lib/python3.7/dist-packages/ipykernel_launcher.py:22: FutureWarning: elementwise comparison failed; returning scalar instead, but in the future will perform elementwise comparison

https://www.sportsbookreviewsonline.com/scoresoddsarchives/nhl/nhl%20odds%202008-09.xlsx

https://www.sportsbookreviewsonline.com/scoresoddsarchives/nhl/nhl%20odds%202009-10.xlsx

https://www.sportsbookreviewsonline.com/scoresoddsarchives/nhl/nhl%20odds%202010-11.xlsx

https://www.sportsbookreviewsonline.com/scoresoddsarchives/nhl/nhl%20odds%202011-12.xlsx

https://www.sportsbookreviewsonline.com/scoresoddsarchives/nhl/nhl%20odds%202012-13.xlsx

https://www.sportsbookreviewsonline.com/scoresoddsarchives/nhl/nhl%20odds%202013-14.xlsx

https://www.sportsbookreviewsonline.com/scoresoddsarchives/nhl/nhl%20odds%202014-15.xlsx

https://www.sportsbookreviewsonline.com/scoresoddsarchives/nhl/nhl%20odds%202015-16.xlsx

https://www.sportsbookreviewsonline.com/scoresoddsarchives/nhl/nhl%20odds%202016-17.xlsx

https://www.sportsbookreviewsonline.com/scoresoddsarchives/nhl/nhl%20odds%202017-18.xlsx

https://www.sportsbookreviewsonline.com/scoresoddsarchives/nhl/nhl%20odds%202018-19.xlsx

https://www.sportsbookreviewsonline.com/scoresoddsarchives/nhl/nhl%20odds%202019-20.xlsx

https://www.sportsbookreviewsonline.com/scoresoddsarchives/nhl/nhl%20odds%202021.xlsx

https://www.sportsbookreviewsonline.com/scoresoddsarchives/nhl/nhl%20odds%202021-22.xlsx

How good is the market predicting the outcomes?

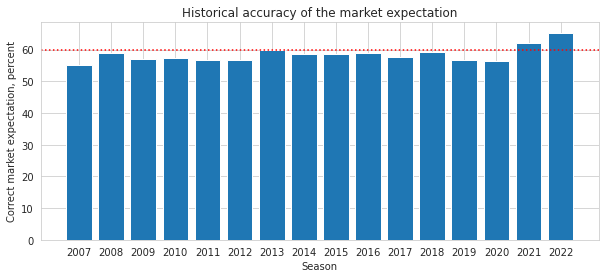

Historically, the market has been accurate about 60% of the time.

seasn_accuracy = round(df_fin.win_pred_home.sum() \

/ df_fin.win_pred_home.count() * 100, 2)

print(f'Market\'s prediction accuracy of the sason {seasn_accuracy}%')

summary_temp = df_fin.groupby(['yr_away']) \

.agg(pred_correct = ('win_pred_home', 'sum'),

games = ('win_pred_home', 'size'))

summary_temp['rate'] = summary_temp.pred_correct / summary_temp.games * 100

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize = (10,4))

plt.bar(summary_temp.index, summary_temp.rate);

plt.axhline(y = 60, color = 'r', linestyle = ':');

plt.xlabel('Season');

plt.ylabel('Correct market expectation, percent');

plt.title('Historical accuracy of the market expectation');

Market's prediction accuracy of the sason 58.49%

At what point the market seems to be correct?

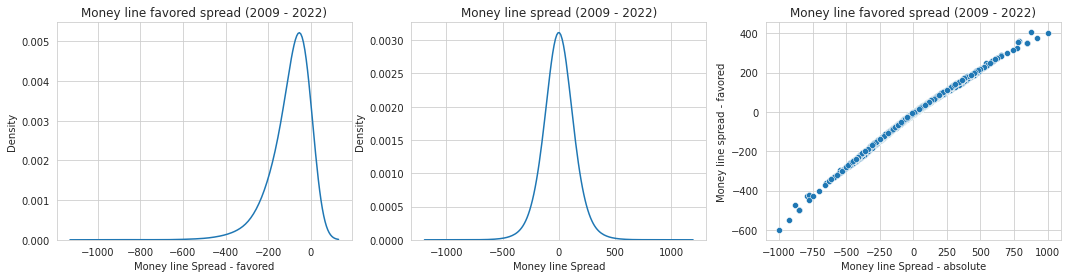

The monely line spread depends on how market is confident in predicting each game. For an agent to make the most optimal and efficient decisions, the agent can examine the equiilibrium of the money line predictiveness. Specifically, in evaluating the difference in money line, the level of confidence the market has on each game’s outcome can be examined.

For each money line (return based on $$$100 investment for losses predicted and amount needed for $$$100 return for wins predicted), I examine how much the market was correct in predicting the outcome. With the iterative process, I can build a response curve and estimate the equilibrium.

I define spread as a magnitude of differential/gap between the projected return and loss when team $g$ win or lose,

$\Delta ML_{g} =

\begin{cases}

(ml_{g}^{own} + 100) - (ml_{g}^{opponent} - 100) & \text{if $ml_{g}^{own} < 0$}

(ml_{g}^{own} - 100) - (ml_{g}^{opponent} + 100) & \text{if $ml_{g}^{own} > 0$}

\end{cases}

$

# if saving the data in long-format

# (a) filter out away team stats

# (b) chagne column names to have common name

# (c) attach game index

# (z) Repeat above for home

# (-) Concat to get the entire game stats

df_fin_away = df_fin.filter(regex = '_away$')

df_fin_away.columns = df_fin_away.columns.str.rstrip('away').str.rstrip('_')

df_fin_away.loc[:, 'gameIdx'] = df_fin.gameIdx

df_fin_home = df_fin.filter(regex = '_home$')

df_fin_home.columns = df_fin_home.columns.str.rstrip('home').str.rstrip('_')

df_fin_home.loc[:, 'gameIdx'] = df_fin.gameIdx

# Attach opponents information

df_fin_away = df_fin_away \

.merge(df_fin_home[['gameIdx', 'Open', 'Close']],

how = 'left', on = ['gameIdx'],

suffixes = ('','_oppo'))

df_fin_home = df_fin_home \

.merge(df_fin_away[['gameIdx', 'Open', 'Close']],

how = 'left', on = ['gameIdx'],

suffixes = ('','_oppo'))

# Stack the dataframe

df_fin_team = pd.concat([df_fin_home, df_fin_away]) \

.sort_values(by = ['gameDate', 'gameIdx']) \

.reset_index(drop = True)

# Calculation on stats for each team

# (A) Boolean stats

df_fin_team.loc[:, 'favorite_win'] = False

df_fin_team.loc[df_fin_team.Close < 100, 'favorite_win'] = True

df_fin_team.loc[:,'favorite_loss'] = False

df_fin_team.loc[df_fin_team.Close > 100, 'favorite_loss'] = True

# (B) Money Line Spread Stats

df_fin_team['spread'] = 0

df_fin_team.loc[(df_fin_team.Close < 0), 'spread'] = \

(df_fin_team.Close + 100) - (df_fin_team.Close_oppo - 100)

df_fin_team.loc[(df_fin_team.Close > 0), 'spread'] = \

(df_fin_team.Close - 100) - (df_fin_team.Close_oppo + 100)

# if both are negative, then we favor the team with better line

df_fin_team.loc[((df_fin_team.Close < 0) & (df_fin_team.Close_oppo < 0)), 'spread'] = \

(df_fin_team.Close + 100) - (df_fin_team.Close_oppo + 100)

# (C) Money line spread for the individual team

df_fin_team['spread_ind'] = 0

df_fin_team.loc[(df_fin_team.Close < 0), 'spread_ind'] = \

(df_fin_team.Close + 100)

df_fin_team.loc[(df_fin_team.Close > 0), 'spread_ind'] = \

(df_fin_team.Close - 100)

# Season order - game number for each team

df_fin_team.loc[:, 'idx_season_prog'] = df_fin_team \

.sort_values(['gameDate_wknd']) \

.groupby(['yr_season', 'team_tri']) \

.cumcount() + 1

# Observing the distribution

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize = (18,4))

plt.subplot(1,3,1)

aryplt = df_fin_team.groupby(['gameIdx']).agg(spread = ('spread','min'))

aryplt = np.array(aryplt.spread)

sns.set_style('whitegrid');

gfg = sns.kdeplot(aryplt, bw_method=0.5);

gfg.set(xlabel = 'Money line Spread - favored',

title = f'Money line favored spread (2009 - 20{last_yr_edge})');

plt.subplot(1,3,2)

aryplt = df_fin_team.spread

aryplt = np.array(aryplt)

sns.set_style('whitegrid');

gfg = sns.kdeplot(aryplt, bw_method=0.5);

gfg.set(xlabel = 'Money line Spread',

title = f'Money line spread (2009 - 20{last_yr_edge})');

plt.subplot(1,3,3)

aryplt_comp = df_fin_team.spread_ind

aryplt_comp = np.array(aryplt_comp)

sns.set_style('whitegrid');

gfg = sns.scatterplot(x = aryplt, y =aryplt_comp)

gfg.set(xlabel = 'Money line Spread - absolute',

ylabel = 'Money line spread - favored',

title = f'Money line favored spread (2009 - 20{last_yr_edge})');

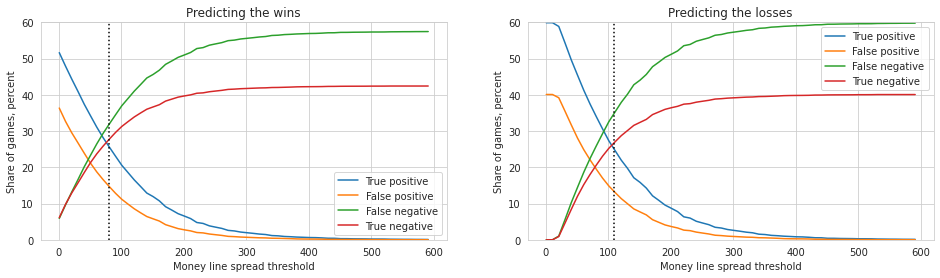

If an agent bets on a team’s win and loss, to what level one should set threshold of money line to minimize the risk? Specifically, what threshold of money line that would maximize true positive and negative?

Below, I compare measure of predictiveness based on a varying level of threshold (the response curves) an agent may use in measuring market’s availability to correctly predict each game’s outcome.

dfsim = pd.DataFrame(np.arange(1, 600, 10).tolist(), columns = ['spread_abs'])

# Evaluate those betted to win:

# true positive, false positive, false negative, true negative

dfsim['tp_win'] = 0; dfsim['fp_win'] = 0

dfsim['fn_win'] = 0; dfsim['tn_win'] = 0

# Same thing for betted to lose:

dfsim['tp_loss'] = 0; dfsim['fp_loss'] = 0

dfsim['fn_loss'] = 0; dfsim['tn_loss'] = 0

# Projction outcome based on spread direction (likely to win/lose)

idx_winproj = df_fin_team.loc[(df_fin_team.spread_ind < 0), ['win','spread']]

idx_lossproj = df_fin_team.loc[(df_fin_team.spread_ind > 0), ['win','spread']]

# For each range

for iter, value in enumerate(dfsim.spread_abs):

# Prediction ---------------------------------------------------------------

# Definitive win

idx_winproj['spread_cut'] = (idx_winproj.spread < (value * (-1))) * 1

# Definitive loss

idx_lossproj['spread_cut'] = (idx_lossproj.spread < value) * 1

# Bit tricky here - logic is to find 'not win' to sort out lose, in using

# the same logical process to filter out relevant predictions

# Logics of the true/false prediction is based on where the threshold lies

# Each logic of confusion matrix goes as following evaluation critera,

# (1) Comparing with true and predicted outcome based on the threshold

# win / loss actual

# win / loss predicted

# (2) Win / loss of true outcomes

# For each condition and mix of the logics dictates the total number of

# games that falls in each criteria

# Evaluation ---------------------------------------------------------------

# Wins

# wins - true positive

temp_condition = (idx_winproj.win == idx_winproj.spread_cut) & \

(idx_winproj.win == 1)

dfsim.loc[iter, 'tp_win'] = np.sum(temp_condition) / np.size(temp_condition)

# wins - false positive

temp_condition = (idx_winproj.win != idx_winproj.spread_cut) & \

(idx_winproj.win != 1)

dfsim.loc[iter, 'fp_win'] = np.sum(temp_condition) / np.size(temp_condition)

# wins - false negative

temp_condition = (idx_winproj.win != idx_winproj.spread_cut) & \

(idx_winproj.win == 1)

dfsim.loc[iter, 'fn_win'] = np.sum(temp_condition) / np.size(temp_condition)

# wins - true negative

temp_condition = (idx_winproj.win == idx_winproj.spread_cut) & \

(idx_winproj.win != 1)

dfsim.loc[iter, 'tn_win'] = np.sum(temp_condition) / np.size(temp_condition)

# Losses

# Losses - true positive

temp_condition = (idx_lossproj.win == idx_lossproj.spread_cut) & \

(idx_lossproj.win == 0)

dfsim.loc[iter, 'tp_loss'] = np.sum(temp_condition) / np.size(temp_condition)

# Losses - false positive

temp_condition = (idx_lossproj.win != idx_lossproj.spread_cut) & \

(idx_lossproj.win != 0)

dfsim.loc[iter, 'fp_loss'] = np.sum(temp_condition) / np.size(temp_condition)

# Losses - false negative

temp_condition = (idx_lossproj.win != idx_lossproj.spread_cut) & \

(idx_lossproj.win == 0)

dfsim.loc[iter, 'fn_loss'] = np.sum(temp_condition) / np.size(temp_condition)

# Losses - true negative

temp_condition = (idx_lossproj.win == idx_lossproj.spread_cut) & \

(idx_lossproj.win != 0)

dfsim.loc[iter, 'tn_loss'] = np.sum(temp_condition) / np.size(temp_condition)

# Plot continuous confusion matrix stats

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize = (16,4))

# For predicting wins

plt.subplot(1, 2, 1)

plt.plot(dfsim.spread_abs, dfsim.tp_win *100, label = 'True positive')

plt.plot(dfsim.spread_abs, dfsim.fp_win *100, label = 'False positive')

plt.plot(dfsim.spread_abs, dfsim.fn_win *100, label = 'False negative')

plt.plot(dfsim.spread_abs, dfsim.tn_win *100, label = 'True negative')

plt.axvline(80, c = 'black', linestyle =":")

plt.xlabel('Money line spread threshold');

plt.ylabel('Share of games, percent');

plt.title('Predicting the wins');

plt.ylim(0, 60);

plt.legend();

# For predicting losses

plt.subplot(1, 2, 2)

plt.plot(dfsim.spread_abs, dfsim.tp_loss *100, label = 'True positive')

plt.plot(dfsim.spread_abs, dfsim.fp_loss *100, label = 'False positive')

plt.plot(dfsim.spread_abs, dfsim.fn_loss *100, label = 'False negative')

plt.plot(dfsim.spread_abs, dfsim.tn_loss *100, label = 'True negative')

plt.axvline(110, c = 'black', linestyle =":")

plt.xlabel('Money line spread threshold');

plt.ylabel('Share of games, percent');

plt.title('Predicting the losses');

plt.ylim(0, 60);

plt.legend();

I look for equilibrium of true positive and true negative based on each threshold of the money line return. I also observe that, while a slight difference, it is much harder to predict and expect return based on the wins (e.g. the equilibrium spread is smaller/narrower) than for the losses. In other words, the market is more certain on outcomes of losses than wins.

One noticeable caveat is the hedging by the market - for example, both teams are favored to win (with money return less than the investment). For those games, for a sake of brevity, I keep the factor simple and treat the market expectations as expectations to win by both teams. The significance in heterogeneous behaviors can be investigate to capture hedging of bets to account for the uncertainty.

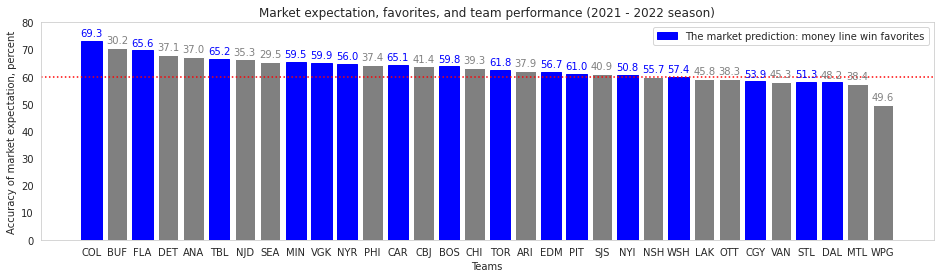

The market is good with their favorites

The market’s predictive power may be endogenously driven by the teams’ overall success,

- Market expects recently or season-wise better-performing teams more likely to win the game

- Market expects recently or season-wise worse performing teams more likely to lose the game

I expect to see the monely line to better predict outcomes of teams with outlier performances (teams with top and bottom quantile of win percentages). The market will have harder time predicting outcomes of average-performing teams. The implication of the finding would suggests that the market does not have additional information that can parse out successful teams in close margin.

team_stats = df_fin_team.loc[(df_fin_team.yr >='2021'), :] \

.groupby(['team_tri']) \

.agg(team_outcome = ('win_pred', 'sum'),

game_count = ('win_pred', 'size'),

favorite_win = ('favorite_win', 'sum'),

favorite_loss = ('favorite_loss', 'sum'),

game_res = ('win', 'sum')

)

team_stats['rate'] = team_stats.team_outcome / team_stats.game_count * 100

# Expectation

team_stats['market_expect'] = 'Win Favorite'

# For those games with hedged money line

team_stats.loc[(team_stats.favorite_win < team_stats.favorite_loss),

'market_expect'] = 'Lose Favorite'

# Sort values for plotting purpose

team_stats.sort_values(by = 'rate', ascending = False, inplace = True)

# Season performance stats

team_stats['rate_game'] = team_stats.game_res / team_stats.game_count * 100

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize = (16,4))

ax.set_axisbelow(True)

plt.ylim((0,80))

plt.grid(axis = 'y')

bars = plt.bar(team_stats.index, team_stats.rate, color = 'grey');

# Color blue for those teams that are generally more favored to win

for i in range(len(bars)):

if team_stats.market_expect[i] == 'Win Favorite':

bars[i].set_color('blue')

plt.legend(['The market prediction: money line win favorites'])

plt.axhline(y = 60, color = 'red', linestyle = ':');

for i, v in enumerate(team_stats.rate):

iter_x = team_stats.index[i];

iter_y = v + 1

iter_s = str(round(team_stats.rate_game[i],1))

if float(iter_s) < 50:

iter_color = 'grey'

else:

iter_color = 'blue'

ax.text(iter_x, iter_y, iter_s, color=iter_color,

fontsize=10, ha='center', va='bottom')

ax.grid(False)

ax.set_xlabel('Teams');

ax.set_ylabel('Accuracy of market expectation, percent');

plt.title('Market expectation, favorites, and ' + \

f'team performance (20{last_yr_edge - 1} - 20{last_yr_edge} season)');

Observing the latest data points, I confirm that the market is better at predicting outcomes of top and bottom performing teams (for 2021 - 2022 season, it would be (a) Colorado, Florida, and Tampa Bay; and (b) Buffalo, Detroit, and Anaheim, respectively).

The market struggles when predicting the ‘middle-of-pack’ teams are much harder on average, showing that the market itself does not have access to the information that can classify better performing teams among the pack.

Does the market predict better as they learn more?

Theoretically, the market is good with learning most up-to-date information to process and make decisions. To examine the theory empirically, I examine if the market’s prediction expectation improves as each season progress.

One intriguing caveat that I show in this exercise, echoing what is absent in the Efficient Market Hypothesis, is that the market is not always right. In fact, in predicting the outcome of NHL games, I show above that the market is slightly better than ‘even-probability’ coin-flips. The hypothesis states that the market expectation is, on average, better than individual agents. Extension of the market inefficiency, I show below, is that the market’s gain in knowledge overall does a little job in improving the outcomes of games as each season progresses.

n_games_reviewed = 82

season_progress_accuracy = df_fin_team \

.groupby(['yr_season', 'idx_season_prog', 'gameIdx']) \

.agg(mkt_accuracy = ('win_pred', 'max')) \

.groupby(['yr_season', 'idx_season_prog']) \

.agg(mkt_accuracy = ('mkt_accuracy', 'mean')) \

.reset_index() \

.pivot('idx_season_prog', 'yr_season', 'mkt_accuracy') \

.head(n_games_reviewed) # Only looking at regular season

# Set an arbiturary quantile range for plotting purpose

# One can test different ranges.

lower_range = 15

upper_range = 85

# Calculate dimension-reducing summary statistics for plotting purpose

x = list(range(1, n_games_reviewed + 1))

# Mean and median: based on the use

x_mu = season_progress_accuracy.mean(axis = 1) * 100

x_me = season_progress_accuracy.quantile(q = 0.5, axis = 1) * 100

# Upper- and Lower-bound range for confidence bend

lb = season_progress_accuracy.quantile(q = lower_range/100, axis = 1) * 100

ub = season_progress_accuracy.quantile(q = upper_range/100, axis = 1) * 100

# Plot

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize = (10,4))

# Line and range

plt.plot(x, x_mu, label = f'Median (2009 - 20{last_yr_edge})');

plt.fill_between(x, lb, ub, color = 'b', alpha = .1,

label = f'Percentile range ({lower_range}% - {upper_range}%)');

# The reference line

plt.axhline(y = 60, color = 'r', linestyle = ':');

# labels and details

ax.set_xlabel('Season game sequence');

ax.set_ylabel('Accuracy of market expectation, percent');

plt.title('No sign of improvements on market expectations as season progresses');

plt.xlabel('Game in season')

plt.xticks(list(range(1,(n_games_reviewed + 1),9)));

plt.legend(loc = 'upper left');

Implications: No fortune telling in NHL

I document evidence that the market expectation for NHL is quite lagging, and the power of expectations mainly comes from extreme and obvious performers (exceedingly outperforming and underperforming teams). A substantial gain based on the bets would require one to ‘beat the market,’ bet against the market, and those expectations to be correct. The evidence shown here fails to show a confidence individual (agents) achieving such outcome consistently to build wealth.

Overall, the findings suggests that the market, having more information available and processed, does not have exceedingly good predictive performance (ceiling at 60%) and cannot improve even as more knowledge is available. This implicates that the predictiveness is impacted by endogenous factors beyond the information available.

Next steps

For NHL specifically, market-adjusting factors like salary cap, limiting roaster space, time on ice, and lineups make the games more in even-playing field. The factors lead to less parity and more overall competitiveness in the league.

As a next step, I introduce commonly used metrics in hockey to measure and explain teams’ success. Relative to the market expectation, I examine the predictive power and explainability based on the given sets of information available in the market.

Relevant resources:

Stefan Szymanski - research and MOOC